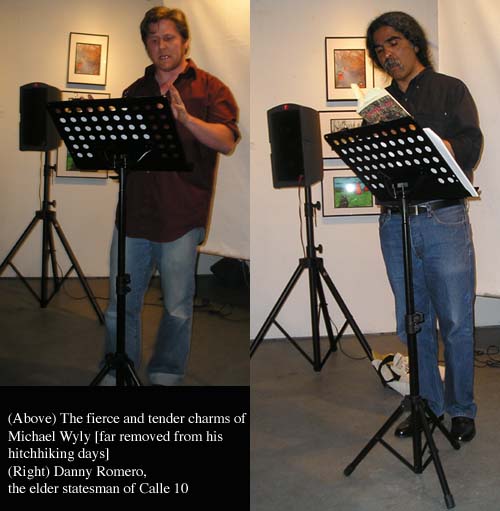

Not quite Batman and Robin, nevertheless, a dynamic duo was featured after the annual SPC members meeting where Bob Stanley (heretofore referred to as the Duke of Poetry) was named as SPC’s fearless leader. That duo was Michael Wyly (from Solano Community College) and Danny Romero (from the other SCC, Sacramento City College).

Bob Stanley, the host, led off the evening by mentioning that Michael Wyly’s wife, Liz, was expecting their first in 2 weeks (not Bob and Liz’s, but Michael and Liz’s . . . you’ve got to sort this stuff out or it might be fodder for the soaps later on). The name was going to be either Ella or Miles. Michael referred to this impending offspring later in the evening as Ella. Was this a tip or a hunch or a hope?

The bulk of Wyly’s poems reflected an international feel. The first of these poems was about Wyly’s observations he made while watching the running of the bulls in Pamplona. He marveled at how the runners weren’t just running to stay ahead of the bulls but how they taunted a precarious fate by making sure they were only a few feet in front of the bulls. Wyly seemed to admire their matador-like courage. In “The Bullrunners” Wyly addresses the bullrunners en masse when he says, “You, this crowd of seekers almost upon the horns . . . caught, violated, supported by gash only.” Wyly’s reflection is that there is near religious dimension to those who run and potentially put their lives in the way of pain in order to understand some metaphysical truth. At the end of the poem, the speaker addresses a more general audience and queries, “What is sound but hooves on the stones? . . . “What are you if you cannot relish this terrible crossing?”

The second poem Wyly described as being a poem about hitchhiking in Ireland. “All Roads Leave” started out with a hitchhiker slogging through the rain when the speaker’s German companion hitchhiker flags down a compact car. The speaker is left behind, and the speaker’s sense of alienation is felt. The speaker reflects on time spent in the hostels of Europe among traveling families and thinking of people he had met on the road. One bedraggled trucker strikes him because the trucker had stopped to give the speaker a lift when he saw the speaker’s hitchhiking sign that said, “Anywhere West.” Back in the hostel the speaker is imagining himself hitchhiking along blackberry hedges as he thinks about the long departed truck driver mentioned previously. The poem ends within this hall of reflective mirrors as the speaker is “measuring the distance all around me.”

The next poem included an epigraph from Michel Foucault’s Madness & Civilization that told of the practice in medieval Europe where the mad, instead of being incarcerated, were put on boats and shipped to the next town where they would be refused and therefore would be sent to the next town ad infinitum. “The Ships of the Madmen” was set on one of these wayfaring boats where the mad are initially strolling on deck, naked (which makes them strikingly similar to some Carnival Cruises). The boat’s denizens struggle with the tides and “the logic of melancholy.” A main speaker appears from this tableau and is “flung below with the pigs.” The main speaker observes he is “drowning already” and is “riding a crest . . . at odds with humans.” Finally, the speaker speculates on his arrival at “The Isle of Man, the land of redemption.” The symbolic freight carried by this actual place provided a poignant ending.

Wyly told how “This Starved Continent” came about as a result of staring into his own reflection while traveling in a train across Europe. Through nearly diaphonous language (“ghosted face in the window . . . halo of passing lights . . . through eyes that hover in glass”), the speaker paints a picture of a singular ego nearly dissolving into the external world around him, yet still curiously holding on to that notion of the self. As the speaker contemplates his “genetic silk” and his “most socialized habits” he remarks at the end that all of these characteristics are a “precursor to self-consumption.” In doing this he acknowledges that the self, and one’s preoccupation with it, is another kind of consumption of image.

“At the Window 3 A.M.” was another contemplative piece. Only this time the speaker did not reflect on the self but the other. This other was a woman whose “mouth in sleep is alien in passivity.” The speaker goes further to describe this woman as someone who “handles the bills and bouts of depression” The woman who is the speaker’s object of discourse is noted for her understanding of her mother’s pain while the speaker contrasts his own understanding as more rudimentary and fragile, “I, a boy, who once saw heaven as a simple understanding.” As the pain and heartbreak intrude on the speaker and this woman, his object of affection, the speaker observes, “To cry from the mouth is to cry for real.”

“Out of Memory” was a apiece that was about Wyly’s grandmother and her struggle with Alzheimer’s. Dossie, which was what his grandmother preferred to be called, was depicted with great care and charity. The central part of the poem is where the speaker remembers a kiss from his grandmother. It was a kiss with “spittle like jewels in the cave of fables. At the end the speaker’s attention turns to his grandfather who says there is nothing left (for her) to do but die.

“Destinations. A Palestinian Boy Thrown Rocks” was inspired by a newspaer story documenting an incident that the title of the poem names very well. The speaker sets the scene, “a concrete chunk neck high” and then psychologizes the young boy throwing the rocks, taking the reader back through some of his formative experiences, the lashings, the meager charity gven to them. In the end, the speaker, though presumably dead, remarks that we are still moving. This statement could be a gesture to Palestinian persistence and if not a figurative call to arms, then a call of empathy for their plight.

Before the final piece Wyly explained that most of the pieces he had read were from a distant time and place and that none of the poems he had read really reflected where he was now. The last poem, “Study of Line” amended that situation. The piece had its origin in a comment that a sculptor friend had made about his sculpture, how it had originated with a line that was repeated and repeated, a motif throughout the solid form. Wyly saw this as a metaphor for writing and how this marked his approach to writing, how when he works he thinks of one line turning. He admitted that since he heard that sculptor friend’s comments, he has become obsessed with the study of line. The poem itself was a deep meditation on a human female form that started with the breast and navigated its way across the expanses of this human female form and finally he observes that her “tenderness is a story of motion.”

The open mic segment served as the intermission between the two feature readings. The first reader (whose name I regrettably missed) read four poems: “If Dreams Come True,” “A Strong Foreboding,” “The Moon,” and “Tropical Paradise”. Bloom Beloved read “Soliloquy from a Wannabe Yogi”

Danny Romero stepped up to the podium and chided that he had indeed remembered to read that night. He then ripped off a zinger stolen from Flannery O’ Connor, who opined that the university doesn’t stifle enough writers. He acknowledged that he stole his wife’s copy of his chapbook of poems because he couldn’t find his copy. Finally, before he launched into his first piece he proclaimed that the theme for the evening’s reading would be “hustling books.”

In “Lessons” the speaker talks about what he has learned, mostly many esoteric bits of life experience which makes the speaker “stand tall” at the end.

“Dreams” begins with a dream where the speaker asks if his father had ever been to Chicago. The father rips off a litany of more harrowing life events that got in the way of that. The speaker’s father saw more of the world than he wanted to with those harrowing events. The speaker offers that his mother liked for his father to stay close to home. This conversation, the speaker contends, was longer than he actually ever had with his father.

The intro to “PCP-dipped Cigarette” provided Romero’s take on one of the great drug innovations of the 70’s, the PCP-dipped cigarette which would allow a person to smoke in public. the problem with this, Romero mused is that when one partook of such a delight at, say, a bus stop, one would still be there four hours later. Then, everyone knew that that wasn’t just an ordinary cigarette. The poem dips into life in hardscrabble LA, how drugs, specifically PCP, were a kind of sanctuary that kept one out of brushes with the law and away from the mental anguish that staying at home brought.

“Identification” was a poem where the speaker recognizes his natural ugliness resembles that of his father’s. The acceptance of this distorted state of bliss provides an insight into a hyperactive self-deprecation.

Romero then read from his novel Calle 10, which Romero described as a rather plotless story about the lives of a bunch of guys living in a house between major episodes in their lives. Romero provided a disclaimer about his book, that it would not be suitable for children. He admitted that Calle 10 was a “dirty book” but that one should probably expect a dirty book to arise out of the lives of three single men living together in a house. The section of the novel Romero read from featured two main characters, Henry and Dude. The antics that Henry and Dude display were considerable. A discussion about the speakers that have just been purchased initiates the scene. Some “weed” is accidentally found and then the scene turns toward “food preparation” where a rat is running across the kitchen and the two characters debate about what is the best way to catch the rat. A trip to a taco truck is discussed and the Henry cautions Dude to “watch out for the motherfuckers out there.” This was a scene that captured the light-hearted moments of desperate lives that have been set within the foreboding realm of the violent inner city.

“The World” was inspired by the small act of grace that Romero’s wife performed when she waited up for him until 10 PM one night to have dinner. This simple act was juxtaposed against “a rotten world filled with rotten people.” The simple truth of the poem’s end is that “the really beautiful is so much more beautiful.”

“A Recipe” was written as a public service for Romero’s brother, Felix, who called up one night to inform Romero that his old lady wasn’t cooking for him anymore. The poem gave detailed, step-by-step instructions on how an absurdist might cook beans. The first step was separating the beans one by one.

Finally, “One Morning in December” posited an imaginary life of the speaker as an Aztec peasant. The speaker imagined meeting Quetzalcoatl and from the perspective of a contemporary man, contemplated the vagaries of being and Aztec Peasant.”

No comments:

Post a Comment